Born on September 7, 1735 in Dunfermline, Scotland, Robert Erskine was an inventor, engineer, ironmaster, and land surveyor. He was awarded a Fellowship in the Royal Society of London (Fellow of the Royal Society) on January 31, 1771 for his many inventions. The Royal Society was a prestigious scientific community of inventors and engineers, and Erskine was nominated to the group by Benjamin Franklin. After spending time thoroughly learning the iron-making process and business, he came to America on June 5, 1771 to oversee the management of the extensive holdings and more than 500 workers of the American Iron Company based at Ringwood. Erskine initially was not impressed by what he saw. In particular, he complained about his new home, stating that "it was patched together at different times creating an awkward architecture." He quickly observed the political and economic condition of Great Britain's North American colonies and made sure the ironworks were productive and financially stable. Erskine operated ironworks at Ringwood, Long Pond, and Charlotteburg from his headquarters.

Erskine's Militia

Colonial Militiaman

As soon as the Revolution broke out, Erskine organized an independent militia (June 1775) to protect the properties he controlled. Known as "Erskine's Independent Company of Foot," its purpose was mainly to protect the valuable ironworks from the British and therefore insure the continuation of iron production so necessary to the Colonial cause. In August of 1775, Erskine was given a commission as Captain of this local militia by the New Jersey Legislature. Founders, forgemen, colliers, and farmers on the property were called to join the militia, varying in size between 45 and 75 men with drilling taking place at both Ringwood and Long Pond. To outfit his militia, Erskine purchased green wool for uniforms as well as shoes, muskets, and bayonets. Additionally, he stockpiled large stores of materials and food supplies for the ironworks and the militia.

Defending The Hudson River

Links of the Hudson River chain at West Point, NY.

Links of the Hudson River chain at West Point, NY.

The British and the rebel American forces both recognized the strategic importance of the Hudson River. If the British were able to control the Hudson Valley and the navigation on the river, they would be able to split the rebellion, dividing New England from the Middle and Southern Colonies.

A Chevaux-de-Frise and a chain to block the river were among the plans authorized by the Continental Congress to obstruct navigation of the Hudson River.

A Chevaux-de-Frise and a chain to block the river were among the plans authorized by the Continental Congress to obstruct navigation of the Hudson River.

Erskine's Marine Chevaux-de-Frise

Image courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

Siding with the patriot cause, Erskine put his talents to work in defending his adopted country. In 1776 he completed a unique design for an underwater defensive device called a Marine Chevaux de Frise. Unlike other devices of the same name, his ingenious yet simple design was a tetrahedron comprised of several oak beams of 32 feet long each, with iron-tipped points or horns on the ends of each beam. Set afloat below the water's surface, this device was intended to pierce the wooden hull of the king’s ships and rotate to continue inflicting damage. Strung together across a channel, they would have been a formidable contrivance which would not injure channels or sensibly obstruct tides.

In a letter to General Scott, dated July 18, 1776, Erskine presented his proposal and recommended that it be used to obstruct the Hudson River. There is no evidence that he even received a reply, let alone that his design was adopted. He also proposed that his invention be put to use in the Delaware River, an idea which was unfortunately rejected by Benjamin Franklin himself. A Chevaux-de-Frise of a different design was already being installed in the Delaware River. The Cassoon Box design that was used in the Delaware River was installed in 1777 in the Hudson River between Plum Point and Polopel Island near New Windsor, north of West Point. The Ringwood Iron Works made the iron points installed at the end of the long log picks for the Polopel Island Chevaux de Frise.

In a letter to General Scott, dated July 18, 1776, Erskine presented his proposal and recommended that it be used to obstruct the Hudson River. There is no evidence that he even received a reply, let alone that his design was adopted. He also proposed that his invention be put to use in the Delaware River, an idea which was unfortunately rejected by Benjamin Franklin himself. A Chevaux-de-Frise of a different design was already being installed in the Delaware River. The Cassoon Box design that was used in the Delaware River was installed in 1777 in the Hudson River between Plum Point and Polopel Island near New Windsor, north of West Point. The Ringwood Iron Works made the iron points installed at the end of the long log picks for the Polopel Island Chevaux de Frise.

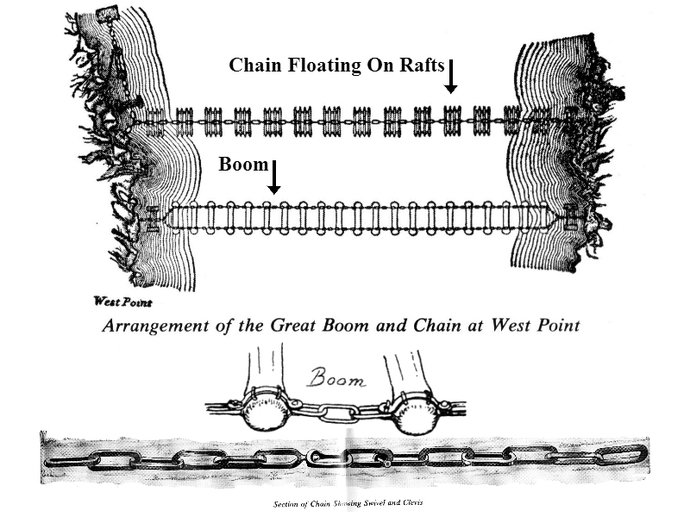

Chaining The Hudson River

In the summer of 1777, the Ringwood Iron Works manufactured iron for a boom intended to be installed in front of Fort Montgomery (Bear Mountain) chain. Over 30 tons of chain links and components were carried by ox cart from Ringwood over the Ramapo Mountains to the Hudson River. Unfortunately for the Americans, the British captured the fort and carried away the chain before the boom could be properly installed.

After the capture of Fort Montgomery, the Ringwood iron was taken to West Point and used to make the boom placed in front of the West Point chain, which was forged at the Sterling Iron Works and placed across the river in 1778.

* Note: The great chain that stretches across the front lawn of Ringwood Manor is not the one of Revolutionary War fame; it was made later and sold to Abram S. Hewitt. Even though Mr. Hewitt probably realized they were a forgery, he kept the links anyway. Regardless, it does give a good idea of what the original huge iron obstacle was like.

After the capture of Fort Montgomery, the Ringwood iron was taken to West Point and used to make the boom placed in front of the West Point chain, which was forged at the Sterling Iron Works and placed across the river in 1778.

* Note: The great chain that stretches across the front lawn of Ringwood Manor is not the one of Revolutionary War fame; it was made later and sold to Abram S. Hewitt. Even though Mr. Hewitt probably realized they were a forgery, he kept the links anyway. Regardless, it does give a good idea of what the original huge iron obstacle was like.

Erskine & the Defense Map Making Agency

One of Erskine's surveys for a road in the Ringwood area.

Perhaps Robert Erskine’s greatest role was that of mapmaker to General Washington. Appointed Geographer & Surveyor General on July 27, 1777, Erskine’s mapping agency produced over 200 accurate and detailed maps for the Continental Army. These detailed drawings are credited with giving Washington superior knowledge of the terrain, enabling him to outmaneuver the British on numerous occasions. The Hudson Highlands map completed in July of 1779 was used by Generals Washington and Wayne to plan the successful American surprise attack on Stony Point. Erskine met with Washington at various army camps throughout the war, including Morristown, Valley Forge, and White Plains, and Washington visited Ringwood several times to discuss what maps and roads were to be drawn by Erskine. Eventually, the mapmaker was able to build up an able staff of assistants, most notably Simeon DeWitt, who would take over the role of Surveyor General after Erskine's untimely death. DeWitt and his family treasured the early maps made by the agency and in 1845 they presented the Erskine-DeWitt collection (approximately 178 maps) to the New York Historical Society, where they are carefully preserved today.

Erskine's Death & the Sale of the Ironworks

Erskine's Grave at Ringwood

According to accounts by his nephew, Ebenezer Erskine, on September 18, 1780, Robert "caught a severe cold and sore throat, which produced a fever..." He died on October 2, 1780 at the age of 45. This was the same day that Major Andre was hanged in Tappan, and it is believed that General Washington did not witness the event because he was at Erskine's bedside. He was buried in the cemetery at Ringwood, alongside his clerk, Robert Monteath, who had died in 1778. Edward Ringwood Hewitt later wrote about Erskine's burial, stating, "It is said that he [General Washington] planted the oak tree which used to stand beside the grave until it was killed by lightning..." Robert Erskine has rested in the cemetery at Ringwood along with more than 150 pioneers, early iron workers, and Revolutionary War soldiers who died marching along the old military road that passed through the site.

In 1782, after Erskine's death and the end of the Revolutionary War, his wife remarried. She and her new husband, Robert Lettis Hopper, Jr. moved to Belleville, NJ. The American Iron Company retained ownership following the Revolution. They sold the Ringwood and Long Pond properties in 1795 to a Pennsylvania business group. Their attempt to revive and operate the property ended in bankruptcy. In 1804, the property was officially transferred to James Lyle, who immediately set about trying to sell it.

In 1782, after Erskine's death and the end of the Revolutionary War, his wife remarried. She and her new husband, Robert Lettis Hopper, Jr. moved to Belleville, NJ. The American Iron Company retained ownership following the Revolution. They sold the Ringwood and Long Pond properties in 1795 to a Pennsylvania business group. Their attempt to revive and operate the property ended in bankruptcy. In 1804, the property was officially transferred to James Lyle, who immediately set about trying to sell it.

RINGWOOD MANOR

1304 SLOATSBURG ROAD

RINGWOOD, NJ 07456

(973) 962. 2240

WEBSITE OWNED & MAINTAINED BY THE

NORTH JERSEY HIGHLANDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

A REGISTERED 501c(3) NON-PROFIT

COPYRIGHT © 2024

1304 SLOATSBURG ROAD

RINGWOOD, NJ 07456

(973) 962. 2240

WEBSITE OWNED & MAINTAINED BY THE

NORTH JERSEY HIGHLANDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

A REGISTERED 501c(3) NON-PROFIT

COPYRIGHT © 2024