"My feelings, my desires, my hopes, embrace humanity throughout the world."

Early Years

Peter Cooper was born in New York City to Dutch parents on February 12, 1791. He was raised in Peekskill, NY. Not given the opportunity for a formal education, Cooper developed a mechanical inclination at an early age. During his youth, he spent considerable time working with his father in various industries because trades were considered more useful than education during the Industrial Revolution. Cooper spent time learning hat-making, brewing, and brick-making. At the age of 17, he became an apprentice to a coach maker in New York City. He later spent time making machines to shear cloth and was the owner of a furniture factory. Because of his natural inclination for tinkering, he referred to himself as a "mechanic" throughout his life.

Making a Name

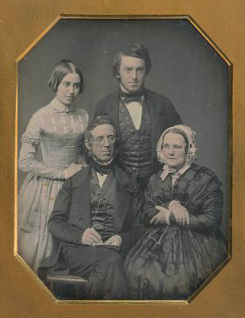

Peter Cooper, his wife, son, and daughter.

On December 22, 1813 Peter married a woman named Sarah Bedell in Hempstead, NY. Peter once wrote of his beloved wife of 56 years that she was his “day star, the solace and inspiration of his life.” But their marriage was not free of hardships in the early years. The couple had six children, but only the last two, Edward and Sarah, lived to adulthood. The young couple did not have enough money for servants, so when Peter returned from work at night, he often found his wife rocking the baby’s cradle and would take over. His engineering mind and the tedious rocking led him to create one of his most ingenious and amusing inventions, the self-rocking cradle, which operated on a pendulum system. Peter took out a patent on the piece in 1815. This was one of many inventions that Peter created during his lifetime. Others included a machine for shaping hubs of wheels, a method of siphoning power from ocean tides, and a rotary steam engine. Sarah and Peter moved to New York City in 1817 and opened a successful grocery store.

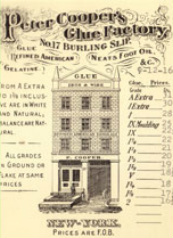

Glue & Gelatin Factory

Cooper again seized opportunity in 1821 when he was informed of a glue factory for sale in the Kipps Bay area. After inspecting the buildings, he agreed to purchase the business. Under his guidance and hard work, the factory grew rapidly. Cooper patented a glue-making process in 1830. His factory also produced gelatin products that were used to clarify wine, make ice cream, candy, and jellies. He invented the first widely-used package table gelatin in America with the help of his wife, who wrote the recipes that were printed on the packets. Today, this gelatin is better known as “Jell-o.” By the mid-19th century, Peter’s business had made him a very wealthy individual and allowed him to move on to his next business venture: iron.

Iron Company

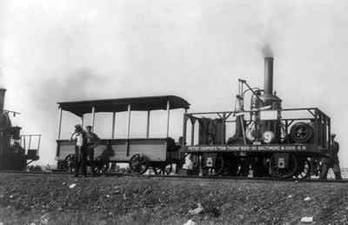

A replica of Cooper's "Tom Thumb."

Peter Cooper relocated his New York City ironworks to Trenton, NJ in 1845. His son Edward and his future son-in-law, Abram S. Hewitt, took over the management of the firm and its expansion at Trenton on the Delaware River. The newly reorganized venture became known as the Trenton Ironworks. The Cooper & Hewitt enterprise seized upon a booming business by providing rails to the expanding railroad industry. The company continued their expansion by purchasing an iron mine at Andover and building blast furnaces at Phillipsburg, NJ.

As a result of his glue factory, iron manufacturing, and real estate investments, Peter Cooper was a self-made millionaire by the outbreak of the Civil War.

As a result of his glue factory, iron manufacturing, and real estate investments, Peter Cooper was a self-made millionaire by the outbreak of the Civil War.

The Atlantic Cable Project

Peter Cooper (left) with members of the Atlantic Cable Projectors.

In March of 1854, Cooper met with some of New York’s wealthiest capitalists to discuss a new venture: laying a cable across the Atlantic Ocean to improve communications with Europe. The men would help provide the financing for the endeavor, which Peter was quite passionate about. The project involved laying communication cable from Valentia, Ireland to Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, requiring the use of two ships because of the bulk of the 2,000 miles of cable. After several failures, the project for laying the Atlantic cable was completed in 1858. Telegraph messages were exchanged between North America and Britain over a period of three weeks before technical problems caused the failure of the cable. Over the next eight years, several more attempts to correct the cable were undertaken. Finally, in 1866, communications resumed and the project was completed.

Creating Cooper Union

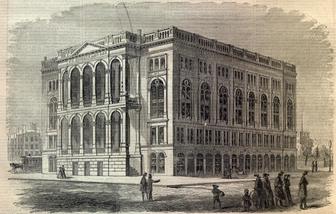

Drawing of Cooper Union c. 1865

Because of his own lack of formal schooling as a child, Cooper had a strong desire to provide education to all people, regardless of their financial ability. He believed that education should be "as free as air and water," and thus set out to create an institution of higher learning: The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Established in 1859 and funded solely by Peter Cooper and donations from relatives and friends, it became one of the first colleges to offer free education to the working classes, including women and children. He strongly believed that education was not only the key to personal prosperity but to civic virtue and harmony as well. Thus, Cooper wanted the school to play an important role in the cultural and political life of the city.

Peter Cooper was closely involved with the overall architecture and design of Cooper Union. The building was constructed of stone and brick. Rolled iron I-beams were used to support the structure. Cooper designed the building to have a Great Hall in the basement with the ability to seat 900 people. This Great Hall quickly became one of the largest open meeting rooms in New York, hosting a wide range of speakers including Abraham Lincoln, Susan B. Anthony, Red Cloud, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, and Henry George. Though Cooper envisioned that the institute would be free and open to all, he realized that not everyone would be able to enroll in courses of study full-time. So he opened a public reading room, allowing citizens of New York to access books, magazines, and periodicals at their own convenience.

Peter Cooper's vision of education inspired many of his peers, including George Peabody, Edwin A. Stevens, Andrew Carnegie, Matthew Vassar, Ezra Cornell, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, to create similar colleges and institutions in the late 19th century. At the time of Cooper's death in 1883, he had poured the majority of his accumulated wealth into Cooper Union.

Today, Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art remains a tuition-free college for accepted students. It has retained its focus on engineering, art, and architecture, and famous figures continue to use the Great Hall for speeches and lectures.

Peter Cooper was closely involved with the overall architecture and design of Cooper Union. The building was constructed of stone and brick. Rolled iron I-beams were used to support the structure. Cooper designed the building to have a Great Hall in the basement with the ability to seat 900 people. This Great Hall quickly became one of the largest open meeting rooms in New York, hosting a wide range of speakers including Abraham Lincoln, Susan B. Anthony, Red Cloud, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, and Henry George. Though Cooper envisioned that the institute would be free and open to all, he realized that not everyone would be able to enroll in courses of study full-time. So he opened a public reading room, allowing citizens of New York to access books, magazines, and periodicals at their own convenience.

Peter Cooper's vision of education inspired many of his peers, including George Peabody, Edwin A. Stevens, Andrew Carnegie, Matthew Vassar, Ezra Cornell, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, to create similar colleges and institutions in the late 19th century. At the time of Cooper's death in 1883, he had poured the majority of his accumulated wealth into Cooper Union.

Today, Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art remains a tuition-free college for accepted students. It has retained its focus on engineering, art, and architecture, and famous figures continue to use the Great Hall for speeches and lectures.

Political Career

Peter Cooper was involved in politics at both the local and national levels. He took a seat on the Common Council in the winter of 1828-29,which he retained until May of 1831. In 1840, Cooper became an alderman of New York City. His greatest contribution during that time was securing a modern water supply for New York, bringing in water from the newly-constructed Croton Aqueduct. Cooper was active in the anti-slavery movement, supported the protection of Native Americans, and promoted concepts to remedy social injustice. He was also a strong backer of the Union during the Civil War.

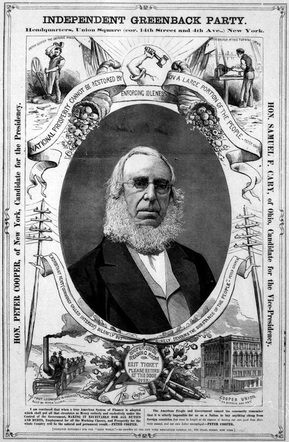

Cooper may be best known for his foray into national politics in 1876. At that time, he strongly disagreed with the financial policies of the government following the Financial Panic of 1873. Cooper advocated for a financial system known as "Greenbackism," which consisted of the circulation of a credit-based, Government-issued paper currency. The first national Independent Greenback political party was formed in 1874 to promote their system as a way to stabilize the national economy. Two years later, Greenback supporters from 18 states met in Indianapolis to nominate the first Greenback candidate for President of the United States--Peter Cooper. He was 85 year old at the time, and remains the oldest candidate to ever run for the office of President. The third-party candidate did not win, bringing in only 82,640 votes.

Cooper may be best known for his foray into national politics in 1876. At that time, he strongly disagreed with the financial policies of the government following the Financial Panic of 1873. Cooper advocated for a financial system known as "Greenbackism," which consisted of the circulation of a credit-based, Government-issued paper currency. The first national Independent Greenback political party was formed in 1874 to promote their system as a way to stabilize the national economy. Two years later, Greenback supporters from 18 states met in Indianapolis to nominate the first Greenback candidate for President of the United States--Peter Cooper. He was 85 year old at the time, and remains the oldest candidate to ever run for the office of President. The third-party candidate did not win, bringing in only 82,640 votes.

Papa Cooper

Peter Cooper was very popular with the citizens of New York. Known affectionately in later years as "Papa Cooper," he lived and died only a few miles from his birthplace. His family was so inspired by his generosity and commitment to philanthropy in the city that they continued to support his causes well into the 20th century.

Papa Cooper remained in remarkable health until April of 1883, when he caught a cold which quickly turned into pneumonia. Peter Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92. The entire City of New York went into mourning, with major newspapers and magazines printing memorials to pay their respects to their beloved citizen. New Yorkers lined the streets during his funeral procession as it made its way to his final resting place, Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Papa Cooper remained in remarkable health until April of 1883, when he caught a cold which quickly turned into pneumonia. Peter Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92. The entire City of New York went into mourning, with major newspapers and magazines printing memorials to pay their respects to their beloved citizen. New Yorkers lined the streets during his funeral procession as it made its way to his final resting place, Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

RINGWOOD MANOR

1304 SLOATSBURG ROAD

RINGWOOD, NJ 07456

(973) 962. 2240

WEBSITE OWNED & MAINTAINED BY THE

NORTH JERSEY HIGHLANDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

A REGISTERED 501c(3) NON-PROFIT

COPYRIGHT © 2024

1304 SLOATSBURG ROAD

RINGWOOD, NJ 07456

(973) 962. 2240

WEBSITE OWNED & MAINTAINED BY THE

NORTH JERSEY HIGHLANDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

A REGISTERED 501c(3) NON-PROFIT

COPYRIGHT © 2024